Canada’s Largest Housing Crash: A Real-Value Perspective

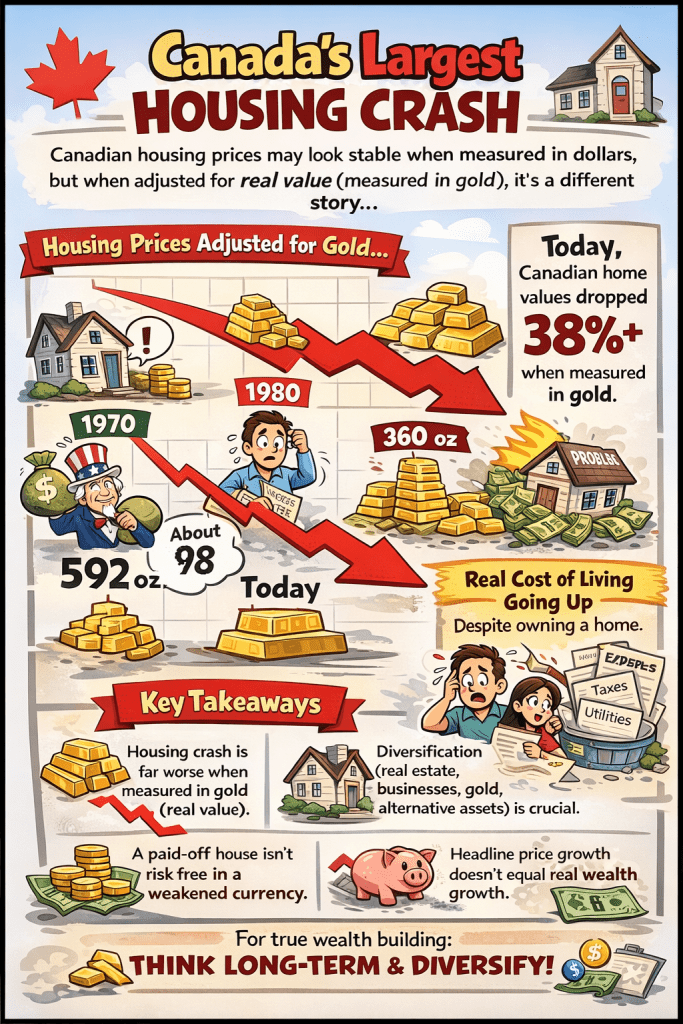

While Canadian housing prices appear relatively stable when measured in dollars, a deeper, long-term analysis suggests that Canada is experiencing one of the largest housing crashes in its history when homes are measured against real money rather than fiat currency. This distinction is central to understanding the argument presented in the discussion.

Nominal Prices vs. Real Value

National housing data shows prices down only about 2–3% year over year, with declines concentrated mainly in Ontario and parts of British Columbia, while many other provinces still show gains. On the surface, this suggests a mild correction rather than a crash.

However, the podcast argues that measuring housing solely in Canadian dollars is misleading, because the dollar itself has lost substantial purchasing power due to decades of inflation and accelerated money creation, particularly since 2020.

Housing Measured in Gold

To address this distortion, the discussion reframes housing values in terms of gold, a long-standing store of value used for thousands of years. When Canadian home prices are measured in ounces of gold rather than dollars, a very different picture emerges.

- In 1970, the average Canadian home cost about 592 ounces of gold.

- By 1980, following the end of the gold standard and high inflation, that figure dropped to 98 ounces of gold, the lowest point in history.

- After recovering partially, Canadian housing peaked again in the early 2000s.

- As of today, the average Canadian home is down approximately 38–40% in gold terms, making this period the second-largest real housing decline in Canadian history, surpassed only by the late 1970s.

Why This Matters

The analysis emphasizes that housing may rise in price without increasing in real wealth. If a home’s dollar value increases while the currency weakens faster, homeowners may feel richer while actually losing purchasing power relative to scarce or global assets.

This has serious implications for Canadians who rely heavily on:

- Paid-off real estate

- Low-yield savings or bonds

- Fixed retirement income

Many homeowners, especially retirees, face rising property taxes, utilities, and maintenance costs that increase faster than their income, even though their homes are mortgage-free.

Risk of Overconcentration in Real Estate

The discussion challenges the common belief that a paid-off home is a low-risk or risk-free asset. In real terms, heavy exposure to a single asset tied to a weakening currency can increase financial vulnerability, especially if that asset does not keep pace with inflation or global stores of value.

Diversification as Risk Management

Rather than viewing volatility as the primary risk, the podcast distinguishes volatility from loss of purchasing power. It argues that long-term risk is better managed through diversification across uncorrelated assets, commonly identified as:

- Real estate

- Dividend-paying businesses

- Precious metals

- Alternative assets such as digital assets

The goal is not speculation, but protecting and growing real wealth over decades, rather than relying on nominal price appreciation.

Key Takeaway

Canada’s housing market has not crashed in the traditional sense of prices collapsing in dollars. Instead, it has experienced a steep decline in real value when measured against sound money. Understanding this distinction helps explain why many Canadians feel financially stretched despite owning valuable property—and why long-term financial resilience depends on perspective, diversification, and real purchasing power rather than headline prices.